Edit 9/20: Added links to Vancouver planner Larry Beasley's comments on tall buildings and DC's Height Act from last year, revealing at the very least an ambivalent attitude toward skyscrapers.

As a follow up to last Monday's post, I'd like to take a bit of a historical excursion to illustrate the effect that zoning has had on Vancouver's downtown commercial district, using that city only as a representative example of many dozens of others throughout North America. The hypothesis that skyscrapers are a necessary adaptation to artificial constraints on commercial space depends upon a showing that space has, in fact, been delineated by legal means, rather than by market forces.

As a starting point, consider this 1898 view of Vancouver, drawn some years after the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway that kicked off an accelerating urban expansion. The city population was only around 26,000 at this point, only slightly greater than nearby Victoria. The commercial heart of the still-unzoned city is outlined in red, and occupies somewhere around 10 to 15 percent of the intensively built urban area:

In the decades following the drawing of this city view, Vancouver's population exploded, topping 100,000 by 1911 and reaching 246,000 in 1931. Notably, in 1927, Vancouver

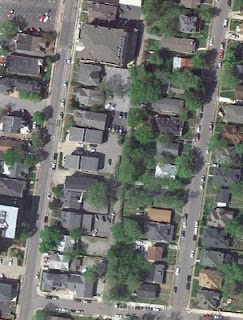

adopted its first Euclidean zoning ordinance, which for the first time designated the single-family residential districts that today cover over 70 percent of the city proper. A 1930s-era aerial view of the downtown (the opposite direction from the previous image) shows what had happened to the central commercial district in the intervening 30 years, again, with the commercial areas outlined in red:

The area containing most commercial activity has expanded by about 6.5 times since 1898 as compared to a population growth of 9.5 times (the industrial areas have grown at a far more rapid rate). There are virtually no high-rise buildings at this point, although the technology to build them had been in existence for at least 30 years. That large commercial buildings had replaced many hundreds of earlier freestanding residential homes is evident by comparing the two images. The pattern of growth is that of a horizontal expansion of a mid-rise urban fabric punctuated by the occasional taller building, rather than a vertical concentration of space near the waterfront.

Eighty years later, the population of the city had more than doubled to

640,000 in a metro area of 2.3 million, representing a metro area increase of 7.8 times, yet the downtown office area had increased by only 1.3 times since the early 1930s. The contemporaneous aerial image below shows the progression from 1898 to 1930 to the present day, with the solid red area representing the 1898 downtown, the outlined red area the 1930 downtown, based on a 1930 zoning map, while the green outline shows expansions of the business district since then, based on a current zoning map and the aerial view:

Vancouver's

zoning map confirms this, showing the downtown district as the small purplish-shaded area in the middle of the top half of the map (a separate height-limited zone covers Eastside, an area that was nearly demolished for highway construction in the 1960s). A handful of retail subcenters to the south, marked in red, contribute some additional land, although their zone's description states an intent to "limit[] the amount of office space." A vast trainyard, zoned industrial (light blue), blocks expansion to the east; the West End, zoned residential, blocks it to the west, with more residential to the south, although with

some limited potential for expansion in the False Creek area:

And just how flexible has the zoning code been to changing needs over the last 80 years? Compare the above to the 1930 plan drawn up by prolific American planning consultant

Harland Bartholomew, who was bluntly given his task by city leaders for whom the moral virtues of the single-family detached home

needed no explanation (p. 60: "

When Bartholomew asked what abuses he should consider in the interim zoning by-law of 1927 he was preparing, the chairman replied that 'the only serious abuse . . . is the intrusion of undesirable apartment houses into residential districts'"):

If the two maps are compared closely, it is possible to see how, overall, there has been virtually no change

in the important boundaries. The combined office/industrial area is nearly identical in both 1930 and in the present map. At most, commercial and residential uses have succeeded small areas of industry in the downtown and parts south (Bartholomew's

most obvious miscalulation -- the presence of excessive amounts of waterfront industrial separating homes from the business district -- was actually the plan's greatest asset, as it inadvertently would permit this limited succession of uses). The single-family areas remain well "protected" against the encroachment of higher value uses in line with the intent of the 1920s planners.

Deprived of space for horizontal expansion, the story of Vancouver's office districts since the 1950s, when construction resumed after a 20-year hiatus, is one of leapfrogging edge cities and debates over height limits. Having spread its population across the entire

Burrard Peninsula in detached homes ever since the arrival of the

streetcars in the 1890s, Vancouver had little land remaining within the city boundaries for large new commercial subcenters, except that now a residential straitjacket held the downtown within strict boundaries. Residential NIMBY-ism, as acute in Vancouver as in any American city, fought tooth and nail against even modest efforts at residential densification, much less expansion of the growing office sector. The pressure cooker shakes and rattles:

"Vancouver’s rapidly accelerating growth and limited building space is forcing planners, builders and community groups to reexamine current height restrictions. Vancouver’s old height restrictions capped downtown buildings at 450 feet, but under new regulations those guidelines have been relaxed up to 650 feet." 10/27/2007

More controversially, the city earlier this year

floated plans to relax height limits in the Eastside area, one of the few remaining large-scale area of the 1920s-era downtown that has not been eradicated by high-rises. The proposed change has drawn very reasonable criticism from several quarters (see

here and

here), yet none that address the fundamental problem: that there is nowhere near enough land available to business uses in Vancouver.

Moreover, the zoning-driven shortage of homes has for some time been increasing demand for high-rise residential towers in the downtown, one of the few places such dense "infill" can be built. With much commercial space having taken flight to the edge cities of Burnaby, Richmond and Surrey, it appears the undersupplied residential may even be capable of outbidding undersupplied commercial in Vancouver's downtown. The long term implications of this trend for the city are apparently of concern to Vancouver's city government.

Now one can certainly make a case that high rises and edge cities might have multiplied in Vancouver regardless of zoning constraints -- the emergence of a large subsidiary center in

Burnaby during an auto era seems predictable given the area's freeway configuration -- but as we see in other cities of the world, where zoning imposes few use-based constraints, mid-rise construction proliferates, with only a handful of scattered towers (Latin American and Japanese cities afford numerous examples). Ed Glaeser has written frequently on the

effect of zoning on housing costs while

extolling skyscrapers -- perhaps a new study could shed light on the link between all three.

Please note, again, that this post is not intended as a specific critique of Vancouver, as the analysis is probably applicable to dozens or hundreds of other cities in North America which fell into zoning's grasp in the 1920s. The city is arguably one of the best-run of its size, having avoided many of the poor decisions made by American cities. The generally applicable nature of the observations here is the important thing.

Vancouver's own planners hesitant to endorse tall buildings: Vancouver planner Larry Beasley last year

praised Washington DC's Height Act, and is

critical of the idea that height is necessary for economic vitality

Further reading:

Zoning and the single-family landscape: large new houses and neighbourhood change in Vancouver (discussing Vancouver's zoning history generally and the city's extraordinary micromanagement of residential zoning in particular).

Nice historic photos of the city over time:

http://aaronwolf.blogspot.com/2011/08/vancouver-over-100-years-of-photographs.html